Christopher Gleadle

Making Education Sustainably Viable – Bridge The Gap

Introduction

The importance of education to well-being and prosperity is clear. The principles and practical application of Sustainable Education are less well understood yet are increasingly recognised as fundamental to addressing the critical global challenges we all face.

In contrast, building a student’s capacity to innovate and problem solve, sustainably viable education can be a powerful tool to re-orient the way we live and work and support a sustainably viable society.

Consequently, vision is a first step towards sustainably viable education. If we don’t know what we want, it is difficult to measure progress or inspire and motivate change. Often it seems easier to know what we don’t want – for example, biodiversity loss, pollution, waste, human rights abuses, marginalisation of minority groups etc. – than to know what we do want to viably sustain. It follows, sustainable viability asks us not only to think more broadly about the immediate impacts of our actions but also to make decisions for the long term.

Moreover, studies have shown successful implementation of sustainability improves morale and retention in business (Sirota 2011), as have they also shown that students who learn in the context of sustainable education are found to be more motivated, better behaved, and more present in class (Hacking, 2010). This suggests sustainable education aspires to educate students to understand how to make decisions that balance the need to preserve healthy ecosystems with the need to maintain vibrant economies and equitable social systems.

However, sustainably viable education is not just a new course; it’s a pedagogy to underpin the curriculum. For, when implemented comprehensively, sustainably viable education will increase student achievement with a firm grasp of how a robust sustainability lens elevates multidimensional systems thinking, problem solving and creativity. Hence this will enrich the interdisciplinary nature of education. As a result, contribute to social, economic, and environmental benefits to the college, its community, and the broader community, as well as proving to be an incubator for business innovation: making it viable, stable, and sustainable.

Accordingly, sustainable viability will reach across disciplines to create competency rather than just knowledge. As a result, provide for skills needed now to fill the gap between education and work, and provide for a changing future.

Competence vs Knowledge

Competence is a broader notion than knowledge. And, in the workplace, competence is more desirable. And, since traditionally, education has focused more on knowledge than competence there is seen by employers a knowledge gap between what the workplace wants and what young people can deliver. For example, I can hear my father now – ‘learning to drive is one thing, learning to drive as a practical driver is another.”

Naturally, in addressing the skills gap, it is important to understand too that competence is bounded by time:

1. The rate of change that makes sector specific knowledge redundant.

2. The rate of change in the education system to keep up with knowledge redundancy.

The gap between the two is the Knowledge Gap – or Competence Gap – of young people leaving education for the workplace in a rapidly changing ultra-competitive world.

Sustainable Viability Matters…

Any healthy, vibrant economy needs innovative businesses that sell goods and services. Against a company’s income it employs staff, pays taxes and contributes to the health and well-being of the society where it resides through its net contribution to the economy. Accordingly, profit is an essential constituent to providing for society and supporting government and its institutions, such as education, to develop eco-systems of equal opportunity and diversity.

And as more and more organisations recognise the financial value to be obtained by integrating sustainability thinking; it follows, as the world realises targets on climate abatement must be reached, sustainability reporting must become more sophisticated to avoid ambiguity and deliver clarity that will deliver discipline and trust. Consequently, this can only happen if the skills and experience needed to capture, create, and deliver validated outcomes are available. Thus, sustainable viability will expand the services of ambitious firms, NGOs and, raise the bar on Governance, as assurance, translation and internalisation of externalities become the game changer for all forms of entity.

For a viable, stable, sustainable economy we need sustainable, viable education that can provide skills:

- Vocational

- Problem Solving

- Transversal

- Mathematical competence

- Science and technology

- Critical thinking

- Imagination

- Entrepreneurial

- Culturally sensitive

Skills that can bridge knowledge gaps and fragmented specialisms to manage the integration of hard and soft systems. Hence, in addition to the above list, education must develop an attitude for completeness and complexity.

If you can’t imagine it, your model can’t capture it, and that means the evidence won’t reflect it.

Consequently, sustainable viability will assist in building future security from visualisation of vulnerability. In brief, vulnerability from:

Physical Risks – damage to physical assets as well as supply chains from climate related weather events such as: storms, floods, strong winds, and heat waves. Additionally, sustainable viability will give vision to long-term environmental trends such as: water availability, rising sea levels and high-risk extraction and recovery of scarce resources.

Competitive Risks – through significant cost increases or cost volatility of key inputs such as: energy, fuel, water, or agricultural products. Hence, related shifts in market dynamics such as a decline in demand for resource intensive products and services; driven by changing customer expectations or legislation.

Regulatory Risks – there is a progression of increased costs and complexity of business from policies and regulations designed to limit the long-term negative impacts on the environment and society and encourage sustainable business operation. Whilst at present there is no binding global treaty, there is an emerging patchwork of legislation at multilateral, national, regional and municipal level. Thus, an ability to cope with scale.1

Reputational Risks – a lack of environmental and social ‘event’ management will damage an organisation’s reputation and so brand value among stakeholders: consumers, investors, policymakers, employees, social groups, and the media. Reaction centred on the perception of an organisation failing to act responsibly and violating voluntary or regulatory codes of practice.

Litigation Risks – there is a rising tide of litigation against organisations for environmental damage, accidental spills, violations of sustainability related legislation. Furthermore, industry and financial regulations are coming under increasing pressure to strengthen and uphold disclosure of environmental and social behaviour delivering greater transparency of operation.

Social Risks – this can result from impacts of and between decisions that may even appear distant. Accordingly, can have immediate impacts close to source, or be in the form of disruption to operations and supply chains from the displacement of climate refugees, conflicts based on resource scarcity such as minerals and water, as well as civil unrest driven by population growth, inequality, or pandemics.

And repeated evidence suggests a positive relationship between sustainability performance and higher financial value. Consequently, as a strategy, it’s about natural and social accounting. But only if full accountability of sustainable life cycle data is audited robustly and synthesised appropriately. Otherwise, it is no more than hot green air!

Accordingly, it is the completeness of sustainable viability where education can add value:

- Internally to understand the risks and opportunities for the school or college environment, enhance the student experience and retention through working within the college facilities as well as reach out to the community and build bridges with business, NGOs and Government.

- Externally as students can work with business as well as public and third sectors to understand sustainable operational systems across a spectrum of work situations relevant to curriculum and integrate those systems with external entities.

It follows, such practical exercises could encompass the identification of current or future environmental challenges and socio-economic shifts that are changing the role of business and institutions in society. This is a chance to listen to others. Seek out those who are involved in day-to-day operations at a business – from the factory floor to strategy groups and R&D. Gather insights from expert colleagues, schools, universities and colleges, consultants, think tanks or NGOs.

In applying three dimensional systems thinking within the curriculum, and applying to practical, day-to-day situations, will elevate problem solving skills, and teach how to measure impact, analyse and synthesise the findings materially. Naturally, this will allow students to understand relevance and meaning, which can then be applied within any workplace position and connections of all actions to their daily lives.

On average across OECD countries, about one in five students is only able to solve very straightforward problems – if any – provided that they refer to familiar situations2. By contrast, fewer than one in ten students in Japan, Korea, Macao-China and Singapore are low-achievers in problem solving. This suggests the UK Economy is suffering the risk of economic vulnerability against competitive countries. I suggest connected Sustainably Viable Education will help place the UK at the forefront for skilled and motivated young people essential to an inclusive economy in a highly charged, highly competitive, resource constrained marketplace.

Developing Competence

While knowledge is required to have competence, it is possible to have knowledge without being competent. Accordingly, competence can be only observed through practical implementation. Yet, within a culture – such as the culture of sustainability – everyone performs and reacts the same. That is what culture means. Accordingly, performance and differentiation become blurred.

And, since competence cannot exist independent of action, in seeking a step change in sustainability to meet the pressing urgency of climate and biosphere action in a just, fair and equitable manner, then naturally, action must be further investigated since action can be further influenced by:

- Experience

- Social cues

- Values

- Behaviours

- Bias

Such effects on actions are usually framed as either cognitive (reason based) of non-cognitive (values, beahviour).3

Accordingly, the idea of sustainably viable education is that, in addition to gaining knowledge in various subjects, a student should get to know their own strengths and understand the opportunities for development. Students become more self-aware; value themselves.

Inevitably, a whole knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes will bolster career choices as well as working as a citizen with a broad competence that transcends and unites different fields of science.

Bridging the Gap

There are standards. However, due typically to poor communication and universal project dislocation, any standards are poorly used, and inadequately communicated. Consequently, of the commonly discussed and disconnected three pillars of sustainability – economic, environmental, and social – greatest attention is paid to the environmental pillar (giving sustainability its green only hue).

As a result, tools, concepts, and principles such as life-cycle assessment, carbon footprint estimation, design for the environment, and product stewardship are becoming more commonplace – though fragmented with no accounting for feedback loops, or relationships between objects and studies, leading to poor reporting. Hence, industry is increasingly considering such measures of performance as greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), resource consumption, solid waste discharges, liquid effluent wastes and toxic emissions and so on into product design, product use and product disposal – yet, without ideal gauges for performance measures as well as audit of operational and accounting cycles and their impact, it is difficult to judge how a change to a product and its value chain affects environmental and social return on investment. The metrics and associated decision-making tools are critical to enabling an organization to measure its progress toward sustainability and authentically communicate its progress to others.

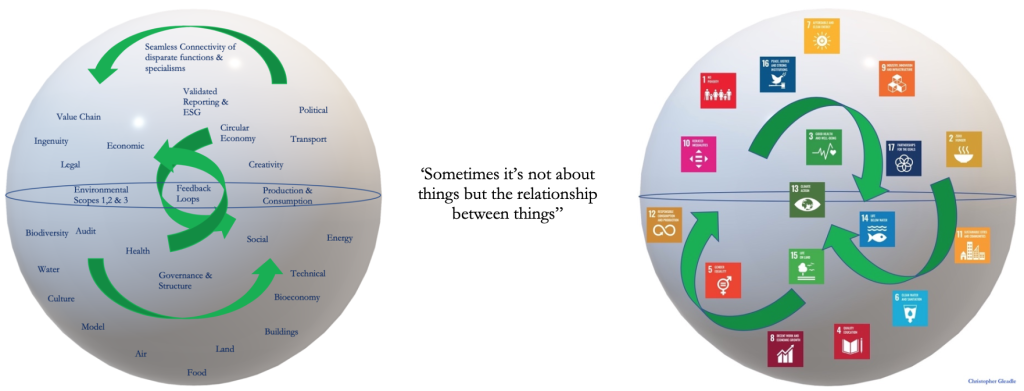

Sometimes, it’s not about things but the relationship between things.

Yet, the social dimension of sustainability is also important to any organization; however, there are many challenges to measuring the social sustainability of production systems. Four interrelated challenges are:

- establishing metrics

- prioritising issues

- identifying and tracking issues in the supply chain

- developing strategies to address social impacts.

There are many possible social impacts to consider within a supply and production system. The United Nations and International Labor Organization (ILO) have developed documents that outline basic expectations for how individuals generally, and workers in particular, will be treated. The ILOs eight core principles address forced labour, child labour, discrimination and freedom of association and collective bargaining.

However, beyond the fundamental rights, it is important to consider metrics that address a broad range of stakeholders or that are specific to products. Community impacts such as improvements to infrastructure or education may be of interest. It may be important to address consumer health and safety considerations for particular products. For example, ambitious organisations may attempt to address the social and psychological impacts of products on consumers, e.g., impacts of smartphones on social behaviors.

Nevertheless, it is not always clear what constitutes improvement. Not unlike environmental sustainability metrics, several measures of social performance must be considered to effectively assess a product, production, or service system. The prisoner’s dilemma4. Or bias5. And, while the previous two are rarely visualised, let alone have impact accounted for, it is also the understanding of tradeoffs and feedback loops that is fundamental to understanding what may be considered sustainable. Accordingly, this brings to light that sustainable viability is about balance as it considers a wide range of stakeholders needs.

It follows that we need to understand what a stakeholder is. A definition: any party that has an interest, financially or otherwise, in an organisation, and is therefore affected by its Governance and performance. Normally this would include managers, employees, customers, suppliers, students, local-communities, pensioners, or other parties affected by its interdependent operations. Their interests do not always coincide.

Naturally, to bridge the skills gap between education and the workplace is to have incoming individuals who understand the ecosystem of sustainability and how it applies to an economic system as well as at an individual level.

Integrated approach to Sustainable Development through curriculum design and organisation

To assist students, gain clarity as to what sustainability is (what it means to one person does not necessarily coincide with another) context and relevance will be important. Accordingly, as an example, carbon foot printing, embodied emissions, water footprint must be connected to the social impacts and connected to financial impact to give context and relevance to curriculum, to college to workplace. It follows, to understand the value of decisions foregone is as important to create appropriate gauges and proportion accurately accountability.6 Without it the figures can be doubtful. As a result, such a practical route will help expand the financial stewardship of education as students gain personal as well as everyday workplace experiences understand where the waste is and do more with less. Not as a cheap throwaway line, but with meaning relevance and understanding.

Young people deserve an education that equips them to be successful students, accomplished professionals, effective parents, and productive leaders in our competitive, and increasingly cooperative, interconnected world. They need the knowledge, skills, and stamina to work individually and collectively to solve current problems and to prevent new ones. They must learn to balance the often-conflicting requirements of society, economy, and the environment to contribute to sustainable viability. And sustainable viability education is a compelling framework within which to learn that it may act as the catalyst for academic achievement, student retention and provide a meaningful context to prepare students for work.

Understandably, it is important to make the change to sustainable viability education simple as well as practical: for administrators and educators. After all, it is our collective task to introduce a sustainability lens and to institute best teaching practices in order to increase our students’ affinities for learning and their ability to excel. Indeed, in adding to the curriculum project-based learning, service learning, and extracurricular activities such as connecting the built environment, food services and facilities operations to learning outcomes, I believe, positively impacts student outcomes, developing communication, collaboration, and critical-thinking skills. It follows, sustainable viability education will provide students multiple ways of acquiring and applying knowledge and skills and offers teachers multiple ways of providing differentiated instruction to narrow the skills gap to career readiness by committing to academic excellence, while developing global competencies, and work-place capacities.

College Buildings and Facilities Management – Do not isolate them.

To consider the provision and well-being of students and staff within buildings it could be seen important to consider not just the buildings but the services, inventory and people who service and use the buildings too. As a result, sustainability will become measured not just from an energy consumption perspective, but as an eco-system that impacts upon the natural world as well as well-being of buildings users. Accordingly, audit will deliver relevance, context, and materiality. Naturally, such a route of discovery could well free funds for more important work of the college: free up the impact of students; reduce waste, water, and other vital resources. Simply by understanding the entire eco-system of building use.

In contrast, carbon foot printing, water use etc., while measured, is poorly understood with results left vague due to lack of veracity, appropriate gauge, and completeness. Hence, it is here where students and staff can work together to create practical experience, in the context of the curriculum, and future work life. The outcome will be to deliver meaning and allow the student to learn and understand the three-dimensional thinking skills, over time, required by the workplace.

For example, it is as important the student and staff understand the relevance in a financial context as it is an environmental one to lower resource use to product and service system cycles. Accordingly, understood from an accounting cycle that what is typically viewed as externalities – thus disassociating environmental and social impacts – are internalised that then visualises the true nature of risk, cost, waste, and opportunity. Such problem-solving skills and application of knowledge will deliver competitive advantage to students and inoculate the workplace against marginalisation of students who may be deemed not academic, but they deliver ever greater worth through heightened problem solving and practical implementation skills and competence.

It follows, that to understand the financial materiality of all impacts is to master how to do more with less. To do better with what you already have. As vital for a school or college to understand as it is for a student. And, to take these analytical skills to the workplace no matter what the students career choice. It will have relevance and meaning to any job and give the student confidence to understand and apply the tools they will learn within the context of curriculum to give them competitive advantage.

It follows, when considering buildings and facilities management it is worth considering the interdependence of:

- Energy and water use

- Internal Environment (campus appeal, health & wellbeing)

- Pollution

- Transport

- Materials

- Waste

- Management Processes

- Inventory

- Supply chain

- Facilities Management

- Food

- Embodied Emissions, waste and impact

- Curriculum

Consequently, unless measurement is taken in a holistic manner that account for feedback loops there will not be relevance, context or materiality…understand the glue that connects all the parts.

Example – Information and Communications Technology (ICT)

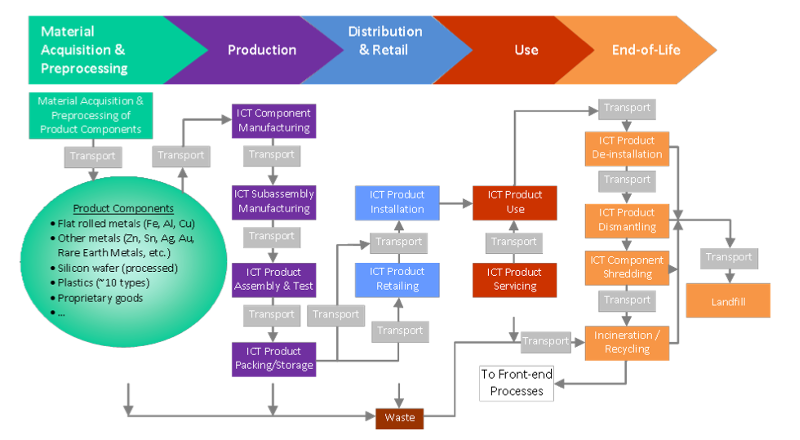

Imagine the LCA (Life Cycle Analysis) of ICT (Fig 1). And let us look at how it fits into the eco-system of buildings and facilities management, the curriculum, energy management, financial management, environmental management, and social management.

Fig 1 LCA of ICT – Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2014

It is clear that all suppliers drag impact on to an establishment. What also becomes apparent is the need to understand the relationship between different life cycle analyses and the impact not accounted for.7 As a result, the first thing we see is the importance to move from price to whole system value. See how the interdependent nature of all decisions, all choices, and the relationship between those choices have on value – for money (and the faith applied to its value), for the environment and for society. The interdependence of choices reaches across administration, educators, staff and students to create an invaluable lesson for the transfer of skills for the students and for the college.

Additionally, what you see quickly is that each and every stage affects the cost to colleges, in terms of social and environmental liability as well as financial cost. Yet, all stages offer opportunity for improvement if each stage is understood, in context, relevancy and materiality – whether human rights abuses from raw sourcing to improved use and disposal costs creating rehabilitation opportunities of income to the college at the perceived end-of-life horizon.

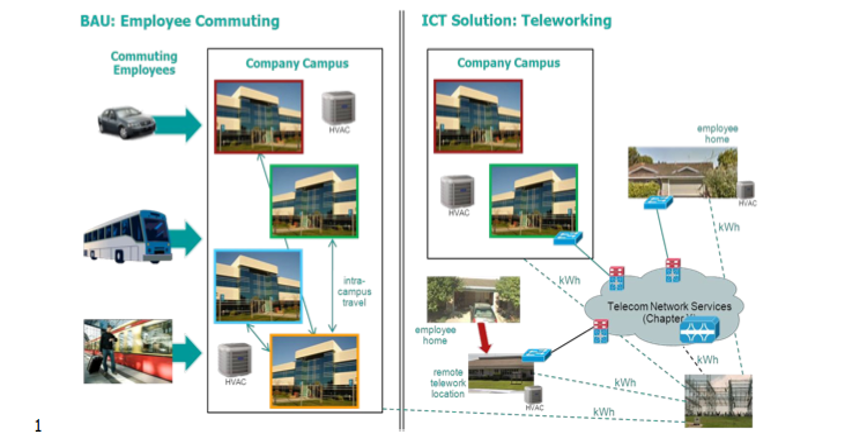

To hone further, reveals enablers of ICT, where improvements can be made to course delivery, student numbers, work placed learning, lowered costs with interdependent environmental and social improvements both within the campus, local, national and international community. See Fig 2

Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2014

ICT enables:

- Avoid student and staff commuting

- Avoid travel when reaching out to community e.g. business collaboration on projects

- Reduce HVAC and lighting load in buildings

- Reduce space requirement – remove / redeploy / let / sublet for income

- Reduce facilities management

- Increase productivity

The above list is not exhaustive, yet we clearly see less need for buildings and less transport but develop greater access to a larger audience for home based, work based, institution-based education. Ultimately, what we see also is for more complete carbon accounting, embodied emissions and waste visualised through feedback loops in use and maintenance as well as water use must be included to understand enablers and associated social impacts. The combination must then be analyzed with a financial context to give materiality. This method can be effectively engaged with cooperation and collaboration across a spectrum of actors including administration, educators, wider staff and student population, local business and social community, other colleges, and so on to all those that have an interest of one kind or another in the college, its performance, and the performance of the students. Ultimately bridging a vital skills gap between education and the workplace.

Summary

Sustainability, and sustainably viable education, is more than being green. It is the understanding of the interdependence of the combined environmental, social and financial aspects and accounting for the feedback loops between actions to understanding how to report in a meaningful and authentic manner to create a viable, stable and ultimately sustainably viable, school, college university, workplace. Sustainable viability in education increases student engagement and enriches the interdisciplinary nature of education (Fig 3 – Sphere Economy). And, while it is highly relevant to bridging the skills gap between education and work life, sustainable viability advances development of problem-solving skills and valuable competence to open eco-systems of equal opportunity and diversity. Consequently, sustainable viability and the sphere economy implemented within education can assist to elevate the college financial performance to free up funds for research and activities as well as attract funding from the business community through outreach activities and its own competitive advantage. It is about being better and being the best that you can.

Fig 3 – The Sphere Economy

1 Money Costs The Earth, C Gleadle, 2018

2 OECD (2014). PISA 2012 Results: Creative Problem Solving: Students’ Skills in Tackling Real-Life Problems (Volume V). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:5OECD (2014). PISA 2012 Results: Creative Problem Solving: Students’ Skills in Tackling Real-Life Problems (Volume V). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264208070-en

3 Some Weird Science Behind Sustainable Viability (2020), and The 5 Essential Steps to Sustainable Viability (2018).

4 The prisoner’s dilemma is a standard example within game theory that shows why two completely rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so.

5 This is very common in all organisations and there are many forms of bias that will impact upon reporting and behaviour. For example, one manger will do what is right for them even if it is not in the best interests of the whole. This often is caused by the way people are rewarded and motivated. But there are others…

6 The 5 Essential Steps To Sustainable Viability, C Gleadle, 2018

7 Embedding Systems Thinking, Tackling The Climate Puzzle, PAF & FNF, 2022